Q: What was the motivation for your research on Arirang?

A: The most common form of Arirang among Koreans and foreigners is the one from a movie based in Seoul. Although there are many variations of Arirang for each region, we still tend to think of them as one and the same. What intrigued me to study Arirang further is this ironic nature of Arirang. One yet many and many yet one.

The first time I got interested in Arirang was in the 1980s, when I first met Mr. Mu, Se-Jung. I participated in his performance of ’Tongmaksal(Unification Arirang)’, his most well-known performance to date, over 60 times. The motif behind this performance piece was that Arirang was an artistic representation of our collective psyche as Koreans. This encounter with Mr. Mu provided me with additional opportunities to participate in Arirang field trips sponsored by <Arirang Association Inc.>. My role as a volunteer in those trips was to produce video recordings and still images of the Arirang performances and artist interviews. Due to financial constraints, hiring professional camera crew was not an option, when we could barely afford then-expensive video cameras.

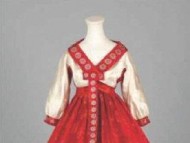

In 1997, <Venture Arirang> was founded in Hanaro-building at Insa-dong, as well as the headquarters of Arirang Association Inc., the organization in charge of performance planning as well as exhibition of Arirang related documents. Being involved in events such as <National Arirang Festival> in 1999 and <Jindo Arirang Exhibition> in 2000, being responsible for adaptation of Arirangs to performance pieces and providing narration for each albums as well as Arirangs themselves required a lot of studying and personal research into the subject.

In due process, I became further interested in the creation of additional materials inspired by Arirang, which involved reinterpretation of archived documents and which resulted in the publication of the book.

Having been appointed as director of organization planning in 1997, I have been involved in the creation of over 10 websites, representing various organizations I have been part of as well as Arirangs themselves. (Kim San’s Arirang, Na Woon-Kyu’s Arirang, Venture Arirang) The official webpage of the organization provide various Arirang related materials in over 60 bulletin boards, which numerous students and scholars are browsing every day for research purposes.

Arirang is subcategorized into over 60 different variations musically, and over 50 variations regionally. Jeong Seon’s Arari has over 7,000 remaining verses and numerous Arirangs based on varying regions and themes exist, including Milyang Arirang, Jindo Arirang, Mungyeong Arirang, Chuncheon Righteous Army Arirang, Daegu Arirang, Yeongcheon Arirang, Gongju Arirang and North Korean Arirang. Arirang serve as a common ground for both people in North and South Korea, as well as those in 180+ foreign nations. Arirang can act as a bonding agent for Koreans worldwide. That’s where the term ’Diaspora Arirang’ came from.

Our people has been using the name Arirang on every possible occasion, be it a brand name or a name of a place, whether humble or noble, from Arirang rubber shoes in the Japanese colonial times, to Arirang #1, the satellite from Korea. Arirang cafe including Arirang pub, Arirang bar, Arirang hotel, Arirang tofu, Arirang kimchi, Arirang radio and Arirang television station. Everything was named after Arirang in Korean history, which had been unprecedented in foreign nations. I believe this phenomenon deserves a place in the world history of culture, as there has been no race who sang the same song in unison. It was further exemplified in 2000 Sydney Olympics, where Korean teams entered during the opening ceremony with Arirang singing in the background, which was welcomed with standing ovation from heads of various foreign nations.

Q: What was your most memorable incident in your research of Arirang?

A: It was when I first heard the meaning of the term ’Arirang-chigi’, a type of crime where multiple culprits attack one person (often under the influence of alcohol) for his money and belongings. (chigi translates to ’hitting’ in Korean) Myself, Arirang Association Inc. and other related cultural organizations petitioned to the media, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Education, Science and Technology and Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism to replace the term with ’Buchuk-bbaegi’ in 2003, on the grounds that it is a remnant of colonial times where Japanese government spread the term to disgrace the national spirit, I went on to appear on television to explain the necessity for revision.

“UNESCO addresses the sponsorship for preserving ’valuable cultural assets around the world’ as the <Arirang Award>. ’Arirang People’ is the term North Koreans use to address all Koreans from the North and the South, including those in foreign countries, Despite these circumstances, the media have been using the term ’Arirang-chigi’ to refer to a violent crime. This is an outrage for all Koreans. We do not want to pass down this disgraceful term as our legacy. This calls for an immediate replacement.“

This term was later revised to ’Buchuk-bbaegi’. For me, to research Arirang entailed being responsible for its preservation as well.

After the above incident was when I concluded that Arirang deserves a more comprehensive approach as ’the song of the people’.

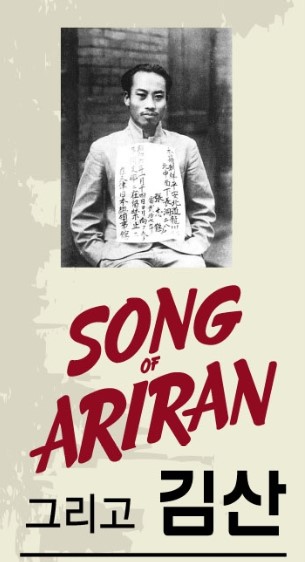

In order to prove academically that Arirang is more than a common folk song, I started a expansive research. Although I originally majored in English literature, I transferred to a college of Korean language and literature in 2001, where I received a bachelor’s degree with my thesis ’Kim San’s ’Song of Arirang’’ in 2004, and went on to enroll in Sungkyunkwan University where I did my research on history of Arirang from modern perspective. (Later I was informed that I was the first person to receive 2 consecutive degrees in Arirang) My academic pursuits were aided by my prior background as a executive of Venture Arirang and over 20 years of experience as a member of Korean Arirang Culture Association Inc., where I was helped by Mr. Kim Yeon-Gap to take my research further. I was helped by movie historian Mr. Kim Jong-Uk while researching the movie ’Arirang’ and its director, Na Yun-Gyu. But most importantly, what kept me going during this research was the publications of my mentor and folk culture scholar Mr. Mu Se-Joong, ’Arirang Theory’ and ’Unification Arirang’. Mr. Mu was also the person who first gave me the reason to study this subject 25 years ago.

Q: What subjects did you explore in your studies?

A: The key focus of my research was to clarify exactly when ’Arirang’ started being the symbol of our people. Arirang went through two major cultural events or changes in the modern times.

The first major event was during the 7 year restoration project on Gyeongbok palace. Around 40,000 people, approximately four times the male population of Hanyang, were forced to work on the project. In this project site, Daewon-gun organized nationwide concerts to soothe the people’s anger and frustration over the forced labor. Various singing groups from all over the nation including professional singing groups who sang Arirang and groups of rafters who build rafts and ride them upstream towards Seoul who sang Arari in their spare time. It was during these times that Arari from Baekdu mountain ranges spread across people from various regions. This was the first major impact in the history of Arirang.

The second impact was when the movie ’Arirang’, directed and produced by Na Yun-Gyu in 1926, was released and in theaters for a significant period of time during the colonial era, which, again, spread Arirang all over the nation.

This thesis focuses on this second major impact in the history of Arirang, and delves further into the musical characteristics and implications of the original soundtrack ’Arirang’. Due to the inherent nature of the music, the music itself was released to the various locales sooner than the movie was released. It could be said that ’the music was what drove the movie to success’. This method of propagation was significantly different from the way other movie soundtracks did. In the same time period when ’Arirang’ was released to public, historical documents claim that ’Euiyeol-dan threw a bomb in the middle of Jongro’. The movie was open during the ’6. 25 Korean War’ and it was played in the tents at the school playgrounds. The movie ran for over 40 years. It is for that reason this research was focused on how Arirang was used as a musical prop in the context of the movie and how it came to be known and spread in and out of the country. These factors contributed to its lengthened time of stay in theaters, and what made its two sequels possible. Moreover, my research explores the process in which Arirang gets solidified as the symbol of the people, thereby concluding the comprehensive analysis of Arirang.

Q: What made you focus on that particular aspect?

A: The first thing this thesis focused on was why Arirang had been known as a mere folk song that has been around for some time. Why was this song sung ’folkishly’?

I started by going through the genealogy of Arirang, and analyzed Arirang as a folk song and as a movie soundtrack based on my interpretation of the genealogy.

To this end, I had to see the movie and the soundtrack from a modern perspective. A lot of research efforts have been devoted to an in-depth understanding of the movie itself and its director.

However, the academics, although the folk song ’Arirang’ and the theme song ’Arirang’, and the theme song ’Arirang’ and the movie ’Arirang’ are fundamentally inseparable, have long been focused on the individual works themselves rather than focusing on their correlations. Unlike prior works, this research focuses on exposing the true identity of ’Arirang’ by exploring how it was transformed in its spreading process as well as its adaptation from folk song to a performance piece. I saw this research as a process of consilience, and therefore took a comprehensive approach to the subject matter. Moreover, I expect to converge different views from various academia including those of Korean literature, cinema, folk culture and music and improve on the prior works.

The Korean literature community focused on the literary values of the lyrics of Arirang, the folk music community approached it from the movie theme song perspective, while the movie community focused on the creators and the cinematic value of the movie. In order to break free from this segregation, I intend to clarify the core characteristics of Arirang by exploring its history of its creation and major changes, as well as its place in the national spirit.

It is also known that due to the intense censorship of the Japanese colonial government, only four out of nine verses of the theme song was sung and passed on. It is under these circumstances that I began my research on this subject in 2002, the year in which the exhibition of historical documents commemorating the 100th Year Anniversary of Na Wun-Gyu’s Birth was commemorated.

Q: How would you summarize your research up to this point?

A: Looking into the post-movie history of ’Arirang’, Arirang as a theme song enjoyed a certain amount of popularity, the cause of which could be traced back to the hybridization of a traditional folk song. Both the movie ’Arirang’ and the theme song ’Arirang’ were the creation of an individual, but it was people’s decision to embrace it as their identity. The interesting question at this point would be what caused the people to do so.

The nine verses that were reorganized to fit the narrative of the movie reached the audience in an intimate level and also left an imprint on them combined with the message of the movie itself. I would answer the question by organizing the key aspects of this phenomenon.

First of all, it is normal for the theme of the movie to be played in the intro, poignant moments, and the ending. However, the lyrics of the theme song was written so that it would suit the specific scenes from the movie and amplify the emotions surrounding them, as well as representing the message of the movie itself. Additionally, the success of the movie ’Arirang’ added to the sense of pride and self-esteem of the people which made the song to be recognized as ’the song of the people’ during Japanese colonial times.

Secondly, the verses from the theme song ’Arirang’ have no connection to one another in terms of context, but based on the connections made from its verses to corresponding scenes, they are able to maintain a certain degree of emotional consistency that is noticeable throughout the movie. Therefore, it can be said that the song ’Arirang’ performed its role by amplifying the emotional impacts of the movie, sustaining the poetic sentiments from respective scenes, bridging the gap between reality and fantasy, and summarizing the whole movie in several verses.

Thirdly, it has been confirmed that there are a total of nine verses in the lyrics of ’Arirang’. Five of those verses were discovered later on. Among these five, the chorus and the first verse are considered relatively common in other folk songs such as ’Sushim-ga’ or ’Sarang-ga’. However, the first verse coming right after the chorus is a style created during Na Yun-Gyu’s adaptations. This pattern was used to embed messages of the movie to each verse, further emphasizing ’the representation of national spirit’ concept. In other words, it can be said that he extended the personal sense of pride and identity to a communal level.

Fourthly, From a folk music historians’ perspective, Arirang’s success can be attributed to following major factors: a) the lyrics of the song were not restricted to a specific purpose, b) the tunes were simple and easy to follow, c) simple lyrical structure – two-line verse and a chorus, and d) versatility – it could be sung as a two-person exchange, a solo, or in unison. Today’s Arirangs sung by Koreans residing in foreign countries were branched out from the original version using the above characteristics.

Fifthly, people were eventually oppressed for singing Arirang after Arirang took on a resistant color. For this reason, the movie and the song were categorized as being resistant, which led to production of various new movies representing such spirit. These resistant elements were the crucial factor in Arirang’s transition in status from ’new folk music’ to ’the original Arirang’ that represents all other Arirangs.

Finally, the theme song Arirang was not a pre-existing version. The lyrics and the tunes were adapted and restructured to fit the thematic elements of the movie. During this period, the western music as well as Japanese musical theories coexisted with the Korean music. While Japanese musical style was being forcefully applied to popular Korean music, Korean people found solace and reaffirmed their identity with Arirang. This adaptation of existing Arirangs to one theme song can be seen as a creative reinterpretation of a historical legacy. Also, surviving the test of time and its constantly changing nature shows that Arirang is very much an open genre as well as resilient.

Q: What are your future research plans?

A: First of all, I intend to expand the scope of my research to the field of folk studies as well as that of Korean literature, to which my original thesis was limited. Also, I aim to focus on the efforts of the successors of Arirang in the post-1980s in terms of creative reinterpretation. I consider Arirang’s transition from a simple folk song to ’the song of the people’ as a form of creative reinterpretation, and will be looking into its development process from a socio-cultural perspective. This will be the focus of my doctoral thesis.

Secondly, I am currently writing a book titled ’People and Arirang’, which will be discussing the spoken accounts of Arirang successors’ lives. The subjects of this research include dancers, painters and photographers as well as singers. After listening to a cappella rendition of Jeongseon Arirang performed by Kim Gil-Ja during ’Jeongseon Arirang Field Trip’ in 1999 and returning to Seoul, many artists have produced various works of art based on Arirang. Notable works include traditional musical version of Jeongseon Arirang by Kim Do-Hu of theater Muyeonsi, modern dance performance ’Arirang’ directed by Kim Gi-In and other Arirang poems and live performances. These passionate works of art were performed on stage during ’99 Korean Arirang Festival’ of October, 1999.

Thirdly, the most famous version of Arirang today is the one used as a theme song, ’Bonjo Arirang’. In recognition of its status, the publication of ’World Arirang Tour’ is under way. I intend to prove the universality of Arirang and thereby laying the groundwork for globalization of Arirang.

Lastly, we need to work on a comprehensive summarization of over ten thousand lyrics of Arirang. We can use this material to create new operas based on Arirang and to give live performances of them in a theater of an international scale, so that people will be able to see Arirang themed performances whenever they want, as long as they meet the pre-arranged schedule.

I believe it is important to ensure that foreigners are able to absorb Arirang themed performance arts whenever they want when they visit Korea, since Arirang is our identity and has already gained a unique status for its universality.

It is a shame that domestic recognition is not on par with Arirang’s worldwide status. There are plenty of research to be done in order to improve upon this issue. (2009 Interview)

1. 문-왜 아리랑을 연구하게 되었나?

답-우리가 일반적으로 알고 있고 외국인이 알고 있는 아리랑은 서울에서 탄생한 영화주제가 ‘아리랑’이다. 그리고 각 지방과 해외에도 여러 지역명을 부친 아리랑이 산재하여 있다. 그런데 우리는 이 많은 아리랑을 하나의 아리랑으로 바라보고 있다. 하나이면서 여럿이고, 여럿이면서 하나인 아리랑.......이러한 아리랑의 다양성에 주목하게 되었다.

직접적으로 아리랑에 관심을 갖게 된 것은 1980년대, 민속학자이시며 세계적인 전위예술가 무세중(Mu SeJung) 선생님을 만나게 되면서, 그의 대표작인 통막살(통일아리랑) 퍼포먼스(통산 60여회)에 참가하게 되었다. 이 작품의 주제의식은“아리랑은 우리 민족정신의 정체성을 표상한다”라는 인식에서 출발한다는 것이었다. 한편 무선생님과 이 작품을 가지고 <사단법인 아리랑연합회>에서 매년 추진하는 아리랑답사 행사에 참여하게 되었다. 이 현장에서 본인은 아리랑 공연과 전승자들의 인터뷰를 영상과 스틸로 담아내는 작업을 자원봉사 해왔다. 당시 매우 열악한 조건(경제적)에서 이루어지는 행사이었기에, 딱히 영상을 담아내는 전문가를 부를 수 없는 상황이었다. 더군다나 그 당시는 카메라와 비디오도 귀할 때이었다.

그후 1997년 인사동 하나로빌딩에 사)아리랑연합회와 함께 공식 후원업체 <벤처아리랑> 회사를 개설하면서 공연기획과 아리랑주제 문헌전시를 주관하게 된다. 1999년 <한민족아리랑제전>과 2000년 진도아리랑전시관 주관, 아리랑주제 작품 무대화, 작품해설, 음반해설을 맡으면서 여러 장르로 확산되는 아리랑과 만나게 되면서 본격적인 아리랑 자료를 수집하고 공부를 하게 되었다.

이 과정에서 ‘아리랑의 컨텐츠화’에 눈뜨게 되어 자료를 찾고, 의미를 부여하고 재해석하여 오늘의 책을 집성하게 되었다. 그 결과에서 사회문화적으로 확산된 아리랑의 다양성에 접하게 되었다.

한편 1997년 단체 사업부 이사로 재직하게 되면서, 단체 홈페이지와 그 외 아리랑 주제 홈피(김산의 아리랑, 나운규의 아리랑, 김산의 아리랑, 벤처아리랑), 아리랑나라 카페 등 10여개의 사이트를 제작하여 운영하여 오고 있다, 단체 홈페이지는 아리랑 주제를 컨텐츠화 하여 각 게시판을 60여개를 지속적으로 운영해오고 있다. 많은 연구자와 학생들이 이 데이터 자료를 기반으로 하여 아리랑 관련 논문을 제출하고 있다.

아리랑은 음악적으로 60여종 지역적으로 50여종이 넘는다. 정선의 아라리는 7천여수가 남아 있고, 밀양아리랑, 진도아리랑, 문경아리랑, 춘천의병아리랑, 대구아리랑, 영천아리랑, 공주아리랑, 북한아리랑 등등, 그리고 남과 북, 180여개국의 해외동포들을 하나로 아우를 수 있는 공동인자이다. 세계로 흩어져 있는 한민족 네트워크를 아리랑으로 묶을 수 있다. 그래서 ‘디아스포라아리랑’이라는 신조어도 나왔다.

우리 민족은 가장 천한 것으로부터 귀한 것에까지 곳곳에 아리랑을 담아서 부르고 있음을 알게 되었다. 일제강점기 아리랑고무신에서부터 지금의 인공위성 아리랑1호까지가 아리랑으로 명명하고 있다. 아리랑카페, 아리랑술집, 아리랑빠, 아리랑호텔, 아리랑두부, 아리랑김치, 아리랑라듸오, 아리랑국제방송, 세상의 만화경을 다 담아 놓은 것이 아리랑이라고 할 수 있다. 이러한 수용 현상은 인류문화사의 맥락으로 연구해야 할 필요가 있다. 이는 어느 나라에도 없는 현상이라고 보기 때문이다. 하나의 노래를 부르는 민족이 지구상에는 없다고 본다. 남과 북으로 허리가 잘린 분단국이지만 1991년 시드니올림픽대회시 아리랑을 단가로 부르며 입장식을 하여 세계 정상들까지도 기립박수를 하지 않았던가?

2.문- 그동안 아리랑을 공부하면서 가장 기억에 남는 일은?

답-이 과정에서 내게 가장 큰 충격을 준 것은, ‘아리랑치기’라는 범죄용어이다. 2003년 이러한 문제제기에 의하여 촉발되어, 범국민적 차원에서 제기되었다, 사)아리랑연합회를 비롯하여 관련 문화예술단체가 연합하여, 각 방송신문 및 각 기관 단체 및 법무부 교육부, 문광부 등에 청원하여, 일제가 우리민족을 폄하하기 위해 조작한 ‘아리랑치기’라는 범죄용어를 ‘부축빼기’로 개정하게 하였다. 처음에는 누구나가 다 불가능한 일이라고 하였다. 신문방송에서도 다루어졌고, TV 방송에도 나가서 이 용어는 개정되어야 한다고 국민들에게 다음과 같이 청원했다.

“세계유네스코에서는 ‘가치 있는 세계 문화유산’ 보존을 위한 지원제도를 <아리랑상>이라는 명칭으로 제정, 시행하여 세계 가치 있는 구비문화 유산의 상징어가 되었고, 북한이 해외 동포까지를 아우르는 개념으로 ‘아리랑민족’이란 용어를 쓰고 있다. 그런데 이러한 아리랑의 위상이 있음에도 불구하고 ‘아리랑치기‘라는 범죄용어를 신문방송에서 일상적으로 쓰고 있는 것은 민족의 정체성을 표상하는 아리랑으로 자기 자신과 민족을 스스로 폄하하는 일이다. 이 시대에서 막지 못하면 그 전과는 다음 세대에 그대로 물려주는 오점이 될 것이기에 시급하게 개정되어야 한다.”

후에 이 범죄용어는 ’부축빼기‘로 개정되었다. 아리랑을 연구한다는 것은 그만큼 책임을 진다는 사실을 알게 해준 일이기도 하다.

이를 기화로 하여 ‘아리랑’이라는 것은 단순한 노래가 아니라 ‘민족의 노래’로서 총체학적인 시각을 가지고 연구해야 한다는 결론을 내리게 되었다.

그래서 아리랑은 ‘민요’라는 편견을 벗고 아리랑은 ‘민요 이상’이라는 것을 학술적으로 규명할 필요가 있어서 통섭적인 연구를 시작했다. 영문학을 전공했지만, 다시 2001년에 국어국문학과에 편입하여 2004년「김산의 ‘Song of Ariran’에 대한 고찰」로 국문학사를 받고, 성균관대학 대학원 국문학과에 입학하여 근대의 시각에서 아리랑의 문화사를 짚어보는 연구를 석사학위논문으로 내놓게 되었다. (아리랑으로 학사, 석사를 이어서 받은 연구자는 처음이라고 한다). 이러한 결과는 나의 직업의식(벤처아리랑 대표)과 이십여년 동안 <사단법인아리랑연합회 Korean Arirang Culture Associati>에서 아리랑연구 편찬사업에 참여하면서 공동 연구자인 김연갑선생의 도움을 받았음이다. 영화<아리랑>과 나운규 연구 부분은 영화사가 김종욱 선생의 도움을 받았다. 그리고 이 과정에서 나의 정신적인 스승이신 민속학자 무세중 선생의 ‘아리랑론’과 ‘통일아리랑’ 작품이 큰 동기부여가 되어 주었다. 25년전 나에게 ‘아리랑’이라는 화두를 처음 던져주신 분이시기도 하다.

3.문- 이번에 아리랑의 어떤 부분을 연구했나?

답-언제부터 아리랑은 ‘민족의 상징’이 되었나? 아리랑은 근대를 거치면서 두 번의 문화충격을 크게 받게 되는 부분에 주목했다.

제1차 문화충격은, 아리랑은 경복궁 중건 7년동안 한양 거주 남자의 4배인 4만명이 동원되었는데, 이 현장에서 대원군은 이들의 원성을 누르고 위로하기 위하여 전국단위의 콘서트 경연대회 마당이 이루어졌다. 여기에서 각 지방에서 위문공연으로 올라온 전문예인집단들이 부르던 아리랑, 그리고 강원도 지역의 뗏군(나무를 베어서 뗏목을 만들어서 타고 와서 서울한강에서 팔았던 화전민이나 농군 집단. 몇 달동안 급류를 타고 오는 도중에 목숨을 잃기도 하는 위험한 업이다.)들이 부르던 아라리들이 경합을 하게 된다, 이 과정에서 백두대간에서 부르는 ‘아라리’가 전국적으로 확산된다. 이때가 아리랑의 첫 번째 문화충격이다.

제 2차 충격은 일제강점기 1926년 나운규가 만든 영화 <아리랑>의 장기상영으로 아리랑이 전국적으로 확산되는 충격이다.

이 논문은 바로 제2차 아리랑의 문화충격 시기를 중점으로 하여서 주제가 <아리랑>의 특성에 대해 집중적으로 연구하였다. 이러한 주제가의 특성으로 하여 주제가가 영화보다 먼저 각 지방에 먼저 상륙했다. 이는 “주제가가 영화를 끌고 다녔다”고 볼 수 있다. 일반적인 주제가와는 전혀 다른 양식으로 인식되고 전파된 것이다. 개봉 당시 상황의 기록을 살펴보면 “종로 한복판에 의열단이 폭탄을 던졌다”라고 표현했다. 영화는 <6.25한국전쟁>시에도 학교 운동장 천막극장에서도 상영되었다. 장장 40여년 이상이나 장기상영되었다. 그래서 이 연구는 주제가 <아리랑>이 영화의 서사구조 속에서 어떠한 영화적 장치로 작용하여 국내외에서 회자되어 확산되었나? 이러한 요인은 영화의 장기상영으로 발전했고, 제2편 제3편의 아리랑이 나왔다고 본다. 나아가 그러한 과정에서 아리랑이 민족의 상징으로서 위상을 부여받게 되는 과정까지 살펴본, 주제가 <아리랑>의 특성 연구이다.

4.문- 왜 그 부분을 주목했나?

답-이 논문에서는 일차적으로 ‘아리랑’을 일반적으로 오래 전부터 불리어진 전통민요로 잘못 알고 있는 점에서 출발하였다, 왜 이 주제가는 ‘민요처럼‘ 불려졌나?

그래서 전승되어 오고 있는 아리랑의 계보를 분석하고, 그 결과를 가지고 주제가 <아리랑>의 형성배경에서, 민요로써의 <아리랑>, 주제가로써의 <아리랑>을 분석하였다.

이를 위해서 나운규가 감독한 영화 <아리랑>과 주제가 <아리랑>에 대해 근대의 시각으로 심도 있게 고찰해 볼 필요가 있다. 그동안 영화 <아리랑>의 작품론, 작가론 등에 대해서는 이미 많은 연구가 있어 왔다.

그러나 민요 ‘아리랑’과 주제가 <아리랑>, 주제가 <아리랑>과 영화 <아리랑>은 불가분의 관계인데도 학계에서는 각각 개별적인 연구에만 머물러 왔다. 이 연구는 사회문화예술에서 확산되는 과정에서 주제가 <아리랑>이 대중문화예술 전범위에서 무대화 되는 과정에서 성격변화를 하여 오늘날 우리가 일반적으로 말하는 ‘아리랑’까지의 정체성을 규명하는 연구이다, <아리랑>에 대한 통섭(consilience)적인 연구로서 총체학적인 시각을 가지고 접근했다. 나아가 선행연구의 문제점을 보완하여 그동안 국문학계, 영화학계, 민속학계, 음악학계 등에서 서로 타자의 입장에서 방치해왔던 주제가 <아리랑>에 대한 총체학적인 연구를 기대해 본다.

국문학계에서는 민요 ‘아리랑’의 텍스트 연구를 중점으로, 민요학계에서는 대중 유행가의 하나로, 민속학계는 영화 주제가로만 인식을 하였고, 영화학계에서는 주제가를 민요 ‘아리랑’이라는 제한성에서 거리를 두어 작가론이나 작품론 등으로만 진행되어 왔다. 이 논문에서는 이러한 점들을 극복하기 위해, 민요 ‘아리랑’에서 주제가 <아리랑>이 형성되고, 확산되는 과정에서 발생되는 성격변화를 거쳐 오늘날 세계 속에서 ‘아리랑’이라고 통칭되는 주제가 <아리랑>의 특성을 규명하고자 한다. 이는 아리랑 연구에 있어서, 첫 번째로 극복해야만 하는 문제제기이기 때문이다.

그리고 이러한 주제가는 일제에 의해서 검열과 탄압으로 총 9절 중 4절만 일반적으로 불려져 오고 전승되어 왔다. 그래서 2002년 <나운규 탄생백주년 기념 문헌전시회>하면서부터 이 연구 논문을 준비해왔다.

5.문-연구 결과 중요한 논점 5가지로 요약한다면?

답-영화 <아리랑>이후, 대중문화예술 속에서 여러 장르로 확산된 아리랑을 살펴보면, 주제가로 불려진 노래로서의 아리랑은 문화변용 현상, 또는 신민요의 혼종적(混種的) 특성에 의해 새로운 노래에 대한 인기를 점할 수 있었다. 영화 <아리랑>과 주제가 <아리랑>은 나운규 개인의 창작작업이었지만, 이를 선택하고 수용한 주체는 ‘민족’이다. 이러한 시각에서 대중주체는 왜 아리랑을 ‘자신의 노래‘로 받아들였나? 에 대해서 문제제기를 해본다.

이는 영화 주제가 아리랑영화의 서사구조에서 재구성한 총 9절의 주제가 <아리랑> 가사를 통해 영화 내적 긴밀성으로 하여 주제가 또는 영화음악으로서 대중에게 각인되어 영화의 주제의식에서 인식되어 출발하고 있음이다. 이러한 시각과 결과는 우리 문화사에 의미 있는 논점들이 되리라고 본다. 이러한 논점들을 정리하는 것으로써, 본 연구의 결론을 삼고자 한다.

첫째, 영화 주제가는 처음의 타이틀과 서정적인 장면에서 그리고 마지막의 앤딩 장면에서 연주되는 것이 일반적이다. 그러나 영화 아리랑 주제가는 영화의 서사 구조에 따라, 그 단락의 상황을 확대 심화시키는 가사를 배치하여 마치 각 대목의 독립적인 삽입곡과 같은 기능을 하게 했고, 전체적인 정서를 함축하여 영화의 테마를 상징하는 기능을 하기도 했다. 이에 영화 <아리랑>은 민족영화로의 성공이 민족과 민중성에 대한 인식과 자각을 더하게 하여 일제강점기 '민족의 노래'로서의 위상을 부여 받을 수 있었다.

둘째, 주제가 <아리랑>은 일반 주제가와 달리 각 절은 탈문맥화 된 내용이다. 그러나 각 절은 영화 내적 기능을 중심으로 상호 연관성을 갖고 영화적 정서를 감싸 안으며 주제를 끌고 나간다. 그리하여 서사의 흐름 속에서 정서를 확대시키는 영화음악의 역할, 서정적인 장면을 유지시키는 삽입곡의 역할, 현실의 고리와 환상의 고리를 이어주는 역할. 그리고 영화 전체를 이미지화 하는 주제가의 역할을 주제가 <아리랑>은 포괄적으로 수행했다고 본다.

셋째, 이러한 역할을 한 주제가 아리랑의 가사는 총 9절로 확인되었다. 이는 기존에 일반적으로 알려진 4개의 절에 나머지 5개의 절이 새롭게 확인된 것이다. 이중 후렴과 제1절은 예전부터 유행가로 불려진 잡가 수심가나 사랑가등에서 확인되는 것으로써, 전렴 다음에 제1절로 배치하여 정형화 하여 특화시킨 것은 나운규의 재창작 작업이라고 볼 수 있다. 특히 주제가 아리랑을 ‘후렴구+제1절’을 ‘공식어구’로 하여 노래를 정형화 하여, 각각의 절에 주제를 집약시켜 ‘민족에 대한 표상’으로까지 확대시켰다. 즉, 나운규는 개인적 자아와 자긍심을 집단적 주체의 단위로 심화 확산시켰다고 볼 수 있다.

넷째, 민요론적인 입장에서 ‘아리랑’이 대중화 할 수 있었던 형식적인 요건은 다음과 같다. ① 특정 기능에 구속되지 않았다 ② 음곡의 단순용이성(單純容易) ③ 두 줄 시에 후렴을 매기는 단순구조 ④ 매기고 받는 합창과 혼자 부르는 독창, 그리고 함께 부르는 제창이 가능하다. 이런 요건에 의해 오늘날 해외 교민사회에서 불려지는 아리랑은 거의 모두 주제가 <아리랑>의 각 편을 수용하여 분화된 것이라 볼 수 있다.

다섯째. 주제가 <아리랑>은 저항의 성격을 띠면서 탄압을 받게 되는 요인이 되었다. 이 때문에 영화 상황과 그 주제가는 일정 기간이 지나면서 저항요로 유형화 되었고, 그 결과 비판과 항일의식을 반영한 여러 각 편이 재생산되었다. 이러한 영화의 저항적 요소는 주제가 또는 ‘신민요 아리랑’에서 모든 아리랑을 대표하는 ‘(본조)아리랑’으로의 위상 변화를 갖게 한 결정적인 요인이 되게 했다.

여섯째, 주제가 <아리랑>은 일반 영화에서처럼 기존 음악을 사용한 것이 아니라 각 국면의 서사 구조에 맞게 가사를 지어 구성하고 기존 선율을 편

속초11.9℃

속초11.9℃ 17.9℃

17.9℃ 철원17.5℃

철원17.5℃ 동두천20.2℃

동두천20.2℃ 파주19.5℃

파주19.5℃ 대관령7.0℃

대관령7.0℃ 춘천17.8℃

춘천17.8℃ 백령도10.6℃

백령도10.6℃ 북강릉10.4℃

북강릉10.4℃ 강릉12.5℃

강릉12.5℃ 동해13.3℃

동해13.3℃ 서울21.5℃

서울21.5℃ 인천18.7℃

인천18.7℃ 원주21.0℃

원주21.0℃ 울릉도13.2℃

울릉도13.2℃ 수원19.5℃

수원19.5℃ 영월15.0℃

영월15.0℃ 충주16.7℃

충주16.7℃ 서산17.5℃

서산17.5℃ 울진12.7℃

울진12.7℃ 청주17.2℃

청주17.2℃ 대전15.6℃

대전15.6℃ 추풍령13.6℃

추풍령13.6℃ 안동15.0℃

안동15.0℃ 상주14.6℃

상주14.6℃ 포항14.5℃

포항14.5℃ 군산17.6℃

군산17.6℃ 대구14.8℃

대구14.8℃ 전주16.8℃

전주16.8℃ 울산13.0℃

울산13.0℃ 창원15.2℃

창원15.2℃ 광주16.4℃

광주16.4℃ 부산14.4℃

부산14.4℃ 통영14.4℃

통영14.4℃ 목포16.4℃

목포16.4℃ 여수14.7℃

여수14.7℃ 흑산도13.9℃

흑산도13.9℃ 완도15.8℃

완도15.8℃ 고창15.4℃

고창15.4℃ 순천15.0℃

순천15.0℃ 홍성(예)17.4℃

홍성(예)17.4℃ 15.4℃

15.4℃ 제주16.1℃

제주16.1℃ 고산16.6℃

고산16.6℃ 성산16.3℃

성산16.3℃ 서귀포18.0℃

서귀포18.0℃ 진주14.5℃

진주14.5℃ 강화17.3℃

강화17.3℃ 양평20.5℃

양평20.5℃ 이천19.3℃

이천19.3℃ 인제13.5℃

인제13.5℃ 홍천17.2℃

홍천17.2℃ 태백8.4℃

태백8.4℃ 정선군11.5℃

정선군11.5℃ 제천15.5℃

제천15.5℃ 보은14.9℃

보은14.9℃ 천안16.9℃

천안16.9℃ 보령17.7℃

보령17.7℃ 부여17.1℃

부여17.1℃ 금산14.7℃

금산14.7℃ 16.6℃

16.6℃ 부안16.0℃

부안16.0℃ 임실15.8℃

임실15.8℃ 정읍16.0℃

정읍16.0℃ 남원15.6℃

남원15.6℃ 장수14.2℃

장수14.2℃ 고창군16.1℃

고창군16.1℃ 영광군15.0℃

영광군15.0℃ 김해시15.1℃

김해시15.1℃ 순창군16.0℃

순창군16.0℃ 북창원15.3℃

북창원15.3℃ 양산시15.1℃

양산시15.1℃ 보성군15.6℃

보성군15.6℃ 강진군15.6℃

강진군15.6℃ 장흥15.6℃

장흥15.6℃ 해남16.0℃

해남16.0℃ 고흥15.1℃

고흥15.1℃ 의령군15.1℃

의령군15.1℃ 함양군14.3℃

함양군14.3℃ 광양시15.0℃

광양시15.0℃ 진도군16.2℃

진도군16.2℃ 봉화13.9℃

봉화13.9℃ 영주15.5℃

영주15.5℃ 문경14.7℃

문경14.7℃ 청송군13.6℃

청송군13.6℃ 영덕13.6℃

영덕13.6℃ 의성14.8℃

의성14.8℃ 구미15.3℃

구미15.3℃ 영천14.0℃

영천14.0℃ 경주시13.9℃

경주시13.9℃ 거창13.4℃

거창13.4℃ 합천14.6℃

합천14.6℃ 밀양15.7℃

밀양15.7℃ 산청13.7℃

산청13.7℃ 거제14.2℃

거제14.2℃ 남해14.8℃

남해14.8℃ 15.7℃

15.7℃

![[음반]북남 아리랑의 전설 [음반]북남 아리랑의 전설](http://arirangsong.com/data/file/news/thumb-3534941659_nLGfd3oc_96fb16793f23322943c3f537882c429a52a5ab05_190x143.jpg)

![[펌] #제11회구미아리랑제 #구미의병아리랑보존회(임규익) #영남민요연구회 구미지회 (2019.04.08) [펌] #제11회구미아리랑제 #구미의병아리랑보존회(임규익) #영남민요연구회 구미지회 (2019.04.08)](http://arirangsong.com/data/file/news/thumb-3534942082_QXRdtyWZ_1f81ac19fd9a4dc91a4191db4de7ee87d2e4a5b5_118x79.jpg)